Trekking as the Bombs Fall

From Blitz-era London to Tehran today, how walking shows the will to live.

When the bombs began to fall on the cities of the United Kingdom in autumn 1940, people took to the streets.

They went not to fight, although thousands of British pilots, air-defense force members, and firefighters did just that. Their goal was simple: to walk out of harm’s way.

German bombers of the Luftwaffe attacked sixteen British and Irish cities between September 1940 and May 1941. Over nine months, they dropped 30,000 tons of bombs, killing more than 40,000 people and damaging around 2 million houses. Naturally, many tried to avoid the bombing.

At the outset of war, official evacuations sent nearly 1.5 million children and mothers from urban areas into the countryside, immortalized by the Pevensie children in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. But amid the Blitz, thousands moved in less formal ways.

The assault created daily, temporary movements of people from urban areas under attack. In a practice that became known as “trekking,” civilians left vulnerable urban areas at night to sleep in safer outlying spaces, returning home in the morning.

Trekking became frequent when the Luftwaffe, having failed to defeat the Royal Air Force, shifted into a pattern of night bombings. The nightly raids created patterns of civilian movement in London and provincial cities like Bristol, Plymouth, Coventry, and Southampton. People fled temporarily in advance of bombings, some on foot, others in buses or trains, returning to their homes and employment the following day.

London families trekked to open spaces like Hampstead Heath, Epping Forest, or nearby Kentish countryside. Some, toting bedding and food, headed for reinforced commercial basements. One such site was a massive underground warehouse in Stepney where up to 14,000 people squeezed into loading bays and vaults. Others found refuge closer to home within nearby church crypts or under railway arches.1

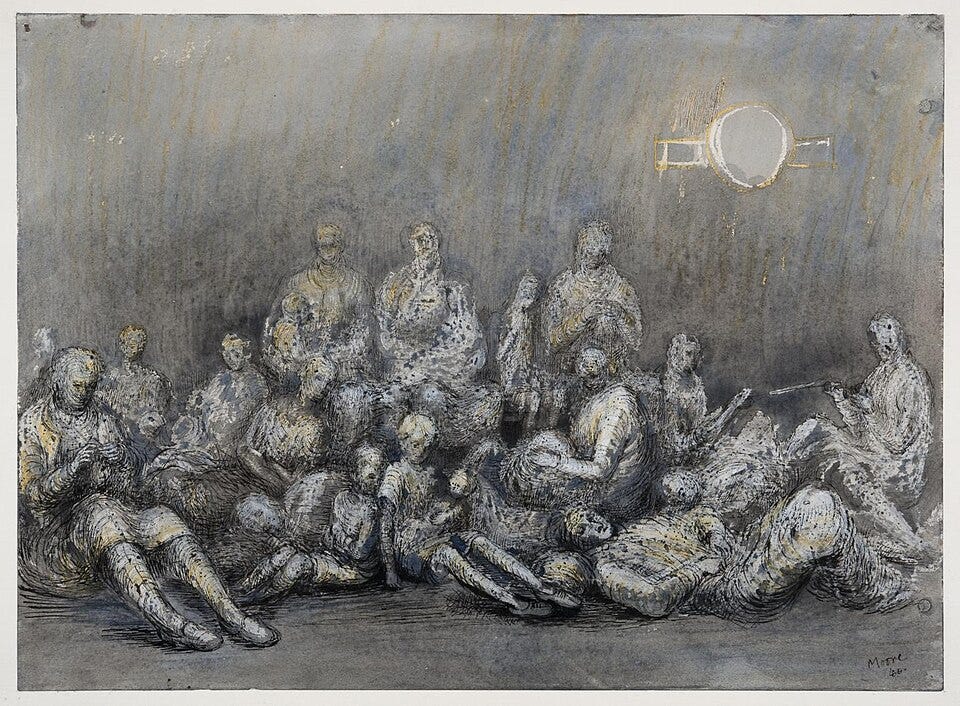

Of course, the most important communal shelters were the stations of the London Underground. Photos of Londoners sitting in the tight quarters of the Tube were shared to demonstrate the city’s grit and its resourceful, stiff upper lip.

But during the initial days of the Blitz, the British government tried to stop Londoners from using the Underground as shelter. It thought disorderly civilians, sprawled upon the platforms, would prevent the movement of commuters and troops. There were also paternalistic concerns about morale. Even as the War Cabinet fled for safety in underground bunkers, it worried civilian Londoners might adopt a mentality of deep shelter, turning into “timorous troglodytes.”2

“As dusk approached each evening, long queues of people, laden with bedding, filed towards the tubes and public shelters.”

After a couple weeks of heavy bombing, the authorities yielded and people were allowed to shuffle down to the platforms. Orderly lines waited outside the stations until 4:00 p.m. when the platforms were repurposed for temporary shelter. By the second week of the Blitz, 150,000 Londoners were walking to a Tube station to spend the night.3

Outside the capital, trekkers were forced to travel beyond city limits. Smaller towns lacked air-raid shelters or outlying suburban areas. So trekking into the surrounding countryside was more common. When Plymouth was attacked in April 1941, a nightly ebb and flow of people between town and country probably reached 50,000 civilians.4

Local governments provided little coordination to support trekkers. And the national government, interpreting trekking as a sign of low morale, did not want to encourage the daily perambulations. Indeed, the Ministry of Information judged trekkers to be of “weaker mental-make up than the rest [of the population].”5

Predictably, the War Cabinet responded with a decree: “'no official arrangements are to be made for persons who are not homeless but who leave the target areas nightly in order to sleep in safer districts.” In Plymouth, trekkers without friends or family in the nearby countryside were forced to find shelter in barns, churches, and quarries. Others slept in ditches, under hedges, or in open fields.6

In the summer of 1941, researchers from the Oxford University Press journal Social Work surveyed towns impacted by the Blitz. They observed that “large crowds departed nightly into the surrounding country districts, where finding no accommodation, they roamed about to the detriment of property, crops and morals.” Despite the lack of accommodation, the journal commended the trekkers for moving “in marvelously orderly fashion.”7

Later study would show that trekking was motivated less by low morale or cowardice than the desire to sleep. In the official British history of the Second World War, Richard Titmuss noted “trekking ensured for most of those who undertook it a good night’s rest.”8

Trekking allowed civilians, especially those in cities lacking underground shelter, to sleep in relative safety while keeping their jobs and supervising their homes. The movement helped keep the British economy and war machine humming, avoiding further labor disruptions during the war.

Leaders were quick to moralize the situation. But the reality was people trying to adapt and survive.

Last Saturday, the U.S. military began airstrikes in Iran. It is the latest American military intervention in the Middle East. And once again the rich men north of Richmond are confident they’ve control of the situation. Recent history suggests otherwise, but we shall see.

One thing certain is the lack of empathy for those forced to endure decisions made from distant war commands.

In 1941 London, fleeing bombs was seen as weakness. In modern American politics, those beneath the bombs—in Iraq, in Syria, in Gaza, and now in Tehran and Tel Aviv—are also viewed with suspicion.

There will be many voices in the coming days as we lurch toward another war. We should listen more to those who move on foot under falling fire, and less to those who launch it from afar.

Geoffrey Field, “Nights Underground in Darkest London: The Blitz, 1940–1941,” International Labor and Working-Class History 62 (Fall 2002): 14–15.

Richard M. Titmuss, Problems of Social Policy, History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Civil Series (London: His Majesty's Stationery Office and Longmans, Green and Co, 1950), 341.

Field, “Nights Underground,” 14–15.

Titmuss, Problems of Social Policy, 307.

Robert Mackay, Half the Battle: Civilian Morale in Britain During the Second World War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 81.

Titmuss, Problems of Social Policy, 306-307.

J. C. Lister, “The War and the People–No. 2: The Nightly Trekker,” Social Work (October 1941): 79–91, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43761142.

Titmuss, Problems of Social Policy, 306-307, 341.

This story is everything I like to read about, thank you!

…it’s nuts…over 50+ armed conflicts going on in the world right now…we should be flying space dragons instead we are still throwing rocks…i don’t see how the empowered should have as much as they do…i don’t understand why we won’t run together…away from these decisions and emotions…some things don’t need sequels or versions…war feels like one…like after the first war we should have all raised our hands and said “woops our bad”…the fart are we doing…