Welcome back to Breakfast Club, stories about life in motion and the ideas that shape our movement through the world.

Movie tropes are slippery.

They slide into a plot, squeezing just beneath your awareness to grease a narrative. Cinematic lubricant, tropes move the story forward such that you barely notice the conceit of all it.

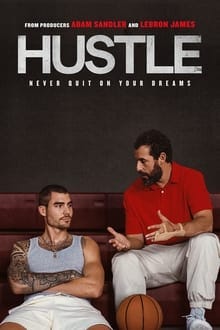

I was reflecting on movie tropes after watching Hustle, a straight-to-Netflix flick starring Adam Sandler as a woebegone talent scout for the Philadelphia 76ers.

The film revolves around the Sandler character’s discovery of Bo Cruz, a talented Spanish basketball player played by Juancho Hernangómez, and the effort to get Cruz into the NBA.

Hustle is an iteration of the classic underdog sports film: an unheralded player from the sticks, in this case a streetball player from the gritty banlieues of western Europe, plucks themselves up into the big leagues with hard work and verve.1

The trope lands midway through the movie.

It’s one that has developed over the last decade or so: ‘the instant web hit,’ wherein a video uploaded online goes viral and creates new opportunities for the protagonists.

In Hustle, Sandler’s scout character struggles to get the player Cruz into the NBA Draft Combine. That is until his Zoomer daughter suggests they film a viral video of Cruz playing streetball.

The gambit works. Social-media buzz carries Cruz into the combine.

Hustle isn’t the first movie to leverage the ‘instant web hit’ trope. The 2014 comedy Chef, a story about a chef who pivots to a food truck business after losing his restaurant job, hinges on the effects of Twitter virality. In the leftist film Sorry to Bother You, the main character parleys a meme of him getting hit with a soda can while crossing a picket line to expose his corporate employer’s evil machinations.

A useful plot device, ‘instant web hit’ elevates the main characters into prominence, lifting them out of a rut or low point for the sake of moving the narrative forward.

This is an optimistic view of technology.

Unable to make it past the traditional gatekeepers of the NBA, Cruz uses social media to appeal directly to the demos, to the people. Much like Maximus “wins the crowd” in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator, leveraging his popularity among the mob to force a tête-à-tête with the villainous Roman emperor, so Cruz uses the weight of social-media chatter to compel the NBA’s powerbrokers to give him a chance.

It’s just a movie, of course. But Hustle relies on presumptions about how social media interacts with sports and society. The ‘instant web hit’ trope assumes that social media is democratic in the best possible way: it rewards athletic merit by elevating talent that would otherwise go unnoticed.

This is the Amazon Reviewification of sports talent, wherein aggregated feedback allows the cream to rise to the top. 200,000 ‘likes’ trumps a couple expert opinions.

Again, Hustle is just a movie. But thanks to the Supreme Court, we can now see how this trope, the instant web hit, is playing out in the real world of sport.

Due to a 2021 Supreme Court decision, the NCAA was forced to change its name, image, and likeness (or NIL) policy, allowing student athletes to profit from sponsorship deals. Fueling the new collegiate-athlete market? The social media attention economy, which provides lucrative opportunities for college athletes to leverage and monetize images of themselves.

The upshot is we now have case studies to see how social media functions to monetize and accelerate the careers of some athletes, while leaving others behind.

Classical and neoclassical liberal economic theorists argue that opening up new markets enables new forms of social mobility.

In this view, social media might reveal previously hidden talent. One can envision talented but unknown athletes, languishing in smaller programs and the lower rungs of the NCAA only because they had fewer opportunities in high school or life more generally. If they’re truly amazing, NIL changes should conceivably allow gains in market power via social virality.

Of course, there is no such thing as a free market. There are always preconditions, biases, and existing power relationships that shape economic interactions.

As one sports agent put it in a piece from Ethan Strauss, the new era of collegiate athletics has more in common with the break up of the Soviet Union than the libertarian utopias dreamed up at George Mason University.

“You had a country that went from all public, government-owned, to complete privatization, and that’s what ended up creating the oligarchs,” Belzer said. “This is what’s happening in college athletics. You have a $10 billion-plus industry, where the labor was getting basically $0, and now they’re going to have an opportunity to make money.”

And one of the more disturbing aspects of this emerging “oligarchy” is how divergently it rewards athletes across gender.

Strauss points out that for female athletes, cash is not flowing exclusively due to talent, but also through sexual appeal.

His piece focuses on Haley and Hanna Cavinder, twins who used TikTok to lift themselves from basketball obscurity at a little-known CSU, to the University of Miami, to millions in NIL endorsement deals.

In many ways, the twins are the vindication of the liberal economists. Plucky upstarts who seized their chance to ditch the Central Valley dust for the glitz of Miami influencerdom. One has to admire their hustle.

But there’s a greasiness throughout the story in Strauss’s telling: billionaires pulling strings to get them to Florida, evocative Instagram posts, the unstated obviousness that their NIL success relied on male sexual fantasy about blonde twins.

In a sense, this is old wine in new bottles.

A NY Times piece on the gendered dynamics of the NIL noted the tension between femininity, markets, and athletic performance “has been part of the deal for female athletes for generations.” Think Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit edition, Katrina Witt, NFL cheerleaders, etc., etc.

Endurance sports are no exception. Strauss quotes Victoria Jackson, a former NCAA 10K champion now professor of history, who remembered how shoe deals fell on better-looking women while runners who made Olympic teams would struggle. Reporting from Sarah Lorge Butler suggests these older tensions are warping NIL money in track and field.

Strauss’s conclusions are more biting:

”There’s the way things are supposed to be, a world in which male and female athletes are genderless machines, and the only thing that matters is how fast, how strong, and how skilled they are. And then there’s the way things really are, a world in which most people who watch sports are dudes with paunches and six-packs of beer. They appreciate girls who can shoot three-pointers, but really, they like girls in bikinis making mindless videos—OnlyFans with a dollop of “wellness.”

In this view, far from elevating new talent, the shift in NIL policies has merely re-affirmed the status quo with all its normative and sexualized preconceptions.

Moreover, by accelerating athlete use of social media, NIL money has quickened the pace in which collegiate sport fractures into a stream of digital representations, increasingly distant from actual athletic acts themselves.

Such was the prescient argument of the French philosopher Guy Debord, who opened his 1967 Society of the Spectacle by observing that in modern production “all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.”

More important than the thing itself is the media image of that thing, especially as that image enables increased commodification.

And so, following Debord’s thesis, the Cavinder twins have moved ever further away from actual sport into pure representation, pure spectacle. A recent GQ profile documents the twins joining a wave of college athletes into scripted professional wrestling.

It is almost emblematic: athletes moving from the pitch to choreographed show-wrestling. We’re moving to a world in which the representation of an athletic act, not the act itself, is the goal—athletic movement completely captured by the theater of kayfabe in service to the market.

Undoubtedly, the NIL policy shift has allowed the vast amounts of money that slosh through collegiate sports to be shared, at least somewhat, with the athletes themselves. But the results don’t seem particularly edifying, at least to me.

Scrolling through the NIL earning rankings is to traipse into the thirst traps of Tik Tok and Instagram. “Amateur athletics” has always been a farce. Now a chunk of it is also degrading.

We’ve accelerated the reconceptualization of sport, activities that we do for well-being and meaning, into a stream of visualizations of bodies in motion, themselves devolved into a series of garish micro-transactions on the Internet.

It’s a social media hustle. And sport is the mark.

Thanks for reading.

Weekly run

Breakfast Club meets every Thursday for an 8-mile run:

When and Where: 6:30am at Lake Temescal in Oakland, CA

Pace: ~7:00 to 7:40 pace with a few hundred feet of climbing

For updates, email Katie Klymko at katieklymko at gmail.com to join Breakfast Club’s WhatsApp chat. More info

For more local events, join our Strava club, East Bay Strava Runners

Posts of the week

That’s it for this week! Thanks for reading. Follow me on Notes, Strava, and what’s left of Twitter.

Hustle may not the most original of sports stories, it’s still a fun watch (with a great training montage). Sandler gives a compelling performance as a weary former-player turned scout and the cast includes numerous actual pro players, lending an authentic glissando to the on-court play. I recommend it!

Really great observations, and I think ties in with the sudden Saudi influence in soccer and golf. If being seen is the most important thing, then instagram important presence is the key