On Keeping a Running Log

Record keeping as staging for the self.

I started my running log in fits and starts.

It was, I think, my sophomore year of high school, and my mother bought me a journal designed for the purpose, a glossy red affair subdivided into days and weeks with a few lines of space to note mileage and time running.

Seared into my mind is the cover with its centered photo of a lower leg impacting the ground, muscles and sinews flexed pornographically.

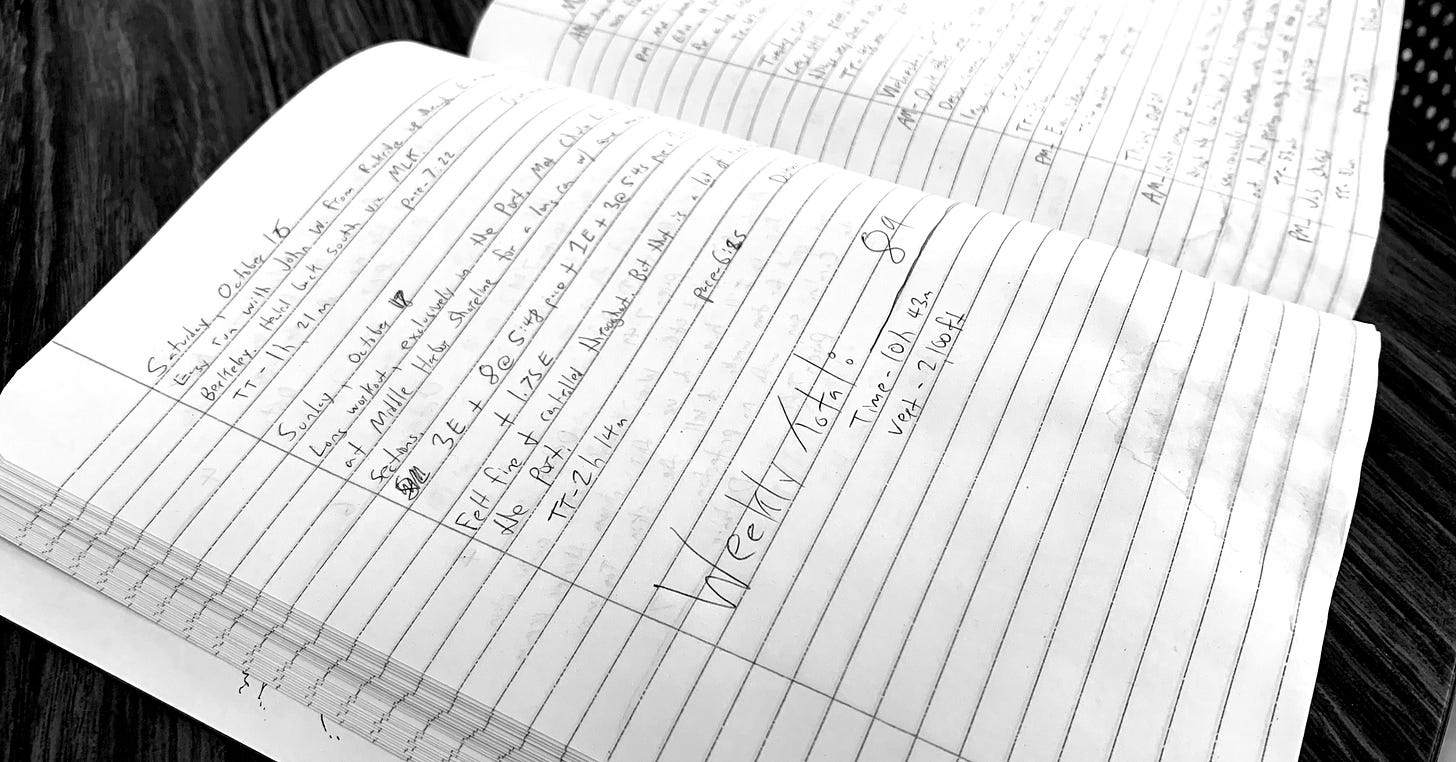

By college, I’d standardized my logging using a basic, no-frills composition notebook, which I dutifully filled with entries for each day. I began each week on the recto (right-side page) of the notebook, concluding on the verso (left-side page) with a tally of weekly mileage.

For the past 21 years, I’ve made that daily entry—2-3 lines of clipped sentences, usually noting where I ran or the details of a workout with metrics of time, distance, and average pace.1 Such is the gist of a log. It’s an accountant‘s view of running: concise summas, written in haste, elaborated only after an important race or amid a pensive mood.

My running log will never be a source of literary value. Indeed, each day's entry is hardly formal language. Mundane observations abound, people and places referred to familiarly and without context. “Out and back to Shi's,” reads a typical entry. “Left ankle still sore. Eric pushed the pace. Stressed from medieval history exam.” There’s insider knowledge here. You'd have to know that “Shi’s” referred to a running route passing the university mansion of Furman’s president in 2004, that my roommate Eric liked to cheerfully push the pace, and that Professor David Spear assigned a lot of secondary reading.

Like all personal notebooks, a running log is written for an audience of one. Joan Didion noted that a private notebook is never created for public consumption. It’s the idiosyncratic record of a mind in flux. “We are talking about something private,” she writes. “About bits of the mind‘s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker.”

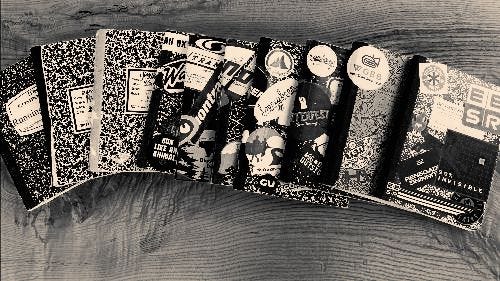

The erratic assemblage of my running log is now a sizable record. It spans eleven notebooks and four (soon to be five) presidential administrations. It takes up half of a bookshelf.

It is also the only artifact of myself that I've maintained with any sort of diligence. What was originally intended as a way to track improvement and training cycles through college has become something else entirely—a record of sorts for a life approaching its midpoint.

Why keep a paper notebook in 2024?

I suppose it’s worth explaining why I still use a paper log. There are certainly easier options to track one’s fitness. Exercise trackers saturate app stores, waiting to suck up movement and biometric data from your phone or Bluetoothed device and transform it into sleek visualizations, brimming with insights and trend lines.

Trackers like Fitbit, Strava, and Apple's various widgets gamify the lived experience of movement with engaging UX design. These products were assembled from the same slurry of Silicon Valley venture capital that was spent to leverage behavioral psychology, computer science, and the world’s best engineering minds into building addictive platforms; social and political degradation mere collateral damage on a relentless path to shareholder value.2

In the same way that contemporary exercise was co-opted by the fitness-industrial complex, so was the humble running log warped by neoliberal trends toward monetizable self-optimization.

But you know all this.

In the Year of Our Lord Anno 2024, it’s too easy to dunk on tech companies. We all know there be monsters beneath the pixelated veneer of a digital interface. And we also know that utility creates ambivalence. Because Strava's training log feature in particular is quite useful. It is, dare I say it, beautiful.

I can scroll through calendars of past activities to find races in the distant past. I can dig deep within workout data or find helpful exercise aggregates. I can see trends indicating an injury on the horizon. It is pleasant and easy to use.

That said, it will never replace my composition notebooks.

This is for a few reasons. First, data is short-lived.

Data is ephemeral, easily lost in the attrition of hard drives, apps, and data-storage plans. The cloud will not be a long-term storage solution: the servers upon which our digital lives depend were not designed for duration. I can easily pull up my paper running log from twenty years ago. My email and instant messages from the same time? Lost forever.3

The physicality of running logs is a feature, not a bug. Silicon is fragile. Paper lasts.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, pen and paper create intentionality.

Handwriting forces a reflective moment in the gap between your mind and the movement of pen between fingers. Quality of penmanship matters little. My own handwriting is a horror: I grip a pen awkwardly, my fingers clasp clumsily around the cylinder. But the sensation of writing—the heft of metal, the scratch against paper, the blur of wet ink smudging against the palm—there’s nothing quite like it.

Unlike the seamless funneling of digital data, the friction between pen nib and pulped woodmatter creates space for the mind to move and dwell. As ink meanders across the page, you become less vulnerable to the inputs of social media, notifications, and the attention economy.

Cal Newport, writing in Digital Minimalism, thinks such tactics help us reclaim the solitude necessary for creative work away from digital distraction. Even in the most quiet of settings, a single push notification can evaporate the creative headspace of being alone with one’s thoughts.

”Solitude requires you to move past reacting to information created by other people . . . Focus instead on your own thoughts and experiences—wherever you happen to be.”

Fitness tracker apps are pure reaction; pretty pixels that contain much information but little knowledge. Pen and paper on the other hand are crucial components in a toolkit for solitude. Because sometimes the words don’t come easy. A blank page sits before you and does nothing.

This is, perhaps, a good thing.

In How to Do Nothing, an exploration of attention and resistance to productivity culture, Oakland artist Jenny Odell argues that one of the cultural problems of our time is finding “little gaps of solitude and silence,” important staging areas for creativity:

“The function of nothing here—of saying nothing—is that it‘s the precursor to having something to say. Nothing is neither a luxury nor a waste of time, but rather a necessary part of meaningful thought and speech.”

The running log—or any notebook or journal for that matter—encourages these precursors to thought and meaningful action. A blank page is exactly the point. We should see a running log then as both backward and forward looking. It is simultaneously recording and staging the past and future self—notation of what’s happened before to reflect upon the opportunities ahead.

Cultivating such space between pages, however old-fashioned it may seem, remains more important than ever.

Thanks for reading. This was originally published in March of 2022 and has been re-edited and updated. Do you keep a log of your fitness or activity? Is it online or physical? What motivates you to keep it going?

Recently from Footnotes

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading.

When I don’t run, I still concisely log the entry as ‘Off’.

For an extended analysis, see Shoshana Zuboff's The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, which critiques the exploitation of personal data by tech companies, wherein human beings play a dual role as both the source of raw data material and the target of manipulation.

Ironically, this period of intense oversharing, wherein billions of humans carry a suite of communication tools in their pocket, might have a paucity of historical sources. Historians, if any still exist in 200 years, may find these decades to be a new Dark Ages as server banks crumble, circuits overheat, and files erode into obsolescence. Everything, the cacophonous calamity of online voices, will crumble into dust.

Great piece. I'm pretty sure my mom got me the exact same running log when I was in high school!

Thank you for this. :) May more people see the value and joy of documenting their runs. My running logs are some of my most treasured possessions.