How Crossing American Streets Became Impossible

Or how 20th-century urban planning still impacts running and walking today.

In February of 1924, Harland Bartholomew, a city planner from St. Louis, stood before the Chamber of Commerce of Oakland, California and proclaimed to a room of local notables that the town’s streets were generally shitty.

The evening had begun as a chipper occasion. It was a period of rapid growth for Oakland and opportunities abounded to shape the future of the city on the San Francisco Bay’s eastern shore. So members of Oakland’s Real Estate Board gathered with the Chamber of Commerce at the glitzy Hotel Oakland to discuss plans to make Oakland a “city beautiful.” The Oakland High School band was even there providing music.

But Bartholomew had a grim prognosis for the growing town. “Conditions are going to constantly depreciate,” he warned, unless the city invested in a general plan for its road system and got serious about fixing its traffic problems, woes would multiply.

“You need larger streets and many more of them,” he concluded succinctly.1 It was a speech that would change Oakland forever.

Given the impact he had on American cities, it’s remarkable how little has been written about Harland Bartholomew. He was a polished man, crisply dressed. A cleft chin gave a slight rugged edge to an otherwise genteel appearance. In photos over the decades, he is always wearing glasses, rounded spectacles that softened the sharp eyes of an engineer.

Trained at Rutgers, his first job in civil engineering mostly consisted of sitting at the sides of bridges conducting traffic counts.2

Imagine a young Harland, age 23, out in the sticky New Jersey summer of 1912, watching vehicles go by. It must have been dreary work, marking tics in a paper log as each automobile and electric streetcar, each horse-drawn carriage and pedestrian passed by.

But perhaps it was formative. Perhaps it shaped his view of the role of infrastructure and the importance of automobility. Perhaps he sat at those bridges and dreamed. Dreamed of a few extra yards of street width relieving bottlenecks, of expanded boulevards speeding up traffic, of completely new roads created to bypass entire cities. Perhaps he dreamed of plans to transport entire populations into a modern world.

If those were indeed his dreams, he would soon be in a position to make them a reality.

Harland’s ascent was rapid. In 1914, at age 25, he became City Planner for Newark. Two years later, he was appointed the city engineer for St. Louis where he opened a consulting firm, Harland Bartholomew & Associates.

From his headquarters in Missouri, he prepared urban plans for over 500 cities around the nation, including St. Louis, Lansing, South Bend, Wichita, San Antonio, Memphis, Louisville, Rochester, Glendale, Peoria, Kenosha, and others. He created transportations plans for Los Angeles, Chattanooga, Grand Rapids, and Washington, D.C. In 1941 President Roosevelt appointed Harland to a committee studying the idea of a national system of highways. The resulting report laid out the vision for the U.S. Interstate Highway System.3

But in February of 1924, he was in Oakland.

Before he arrived, The Oakland Tribune gushed that the East Bay would soon be visited by the “master mind of the St. Louis city plan.” Missouri voters had just approved a massive $88,000,000 bond to enact Bartholomew’s plan.4 Much like the residents of St. Louis, Oakland’s citizens were captivated by the City Beautiful reform movement which swept over North American cities with an emphasis on monumental grandeur.5 City planning was in vogue. And Harland Bartholomew was a city planner who got things done.

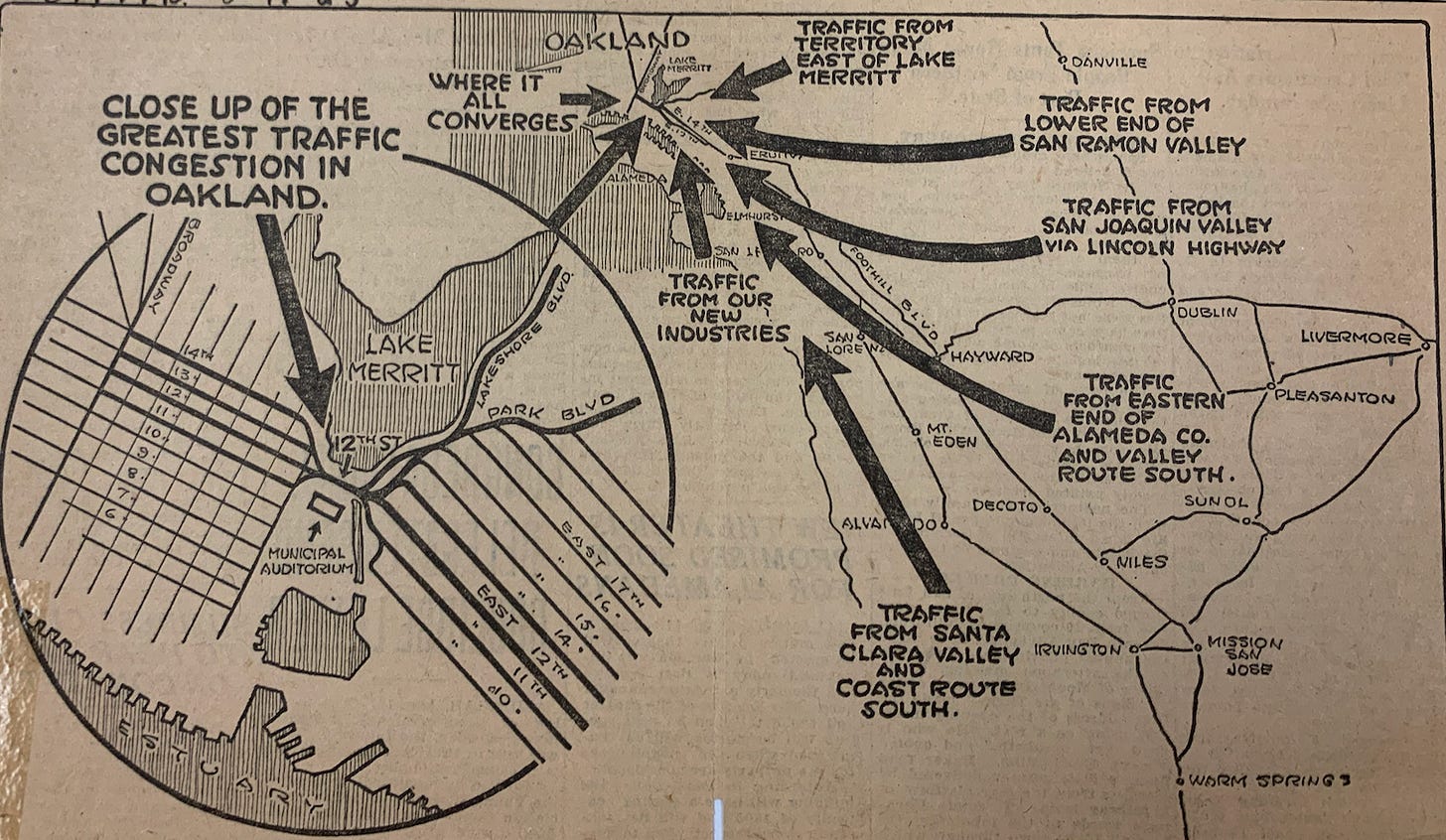

Oakland needed wider streets, he said. But where, exactly? In his speech, Harland called out one road in particular: 12th Street, which passed over a narrow finger of Lake Merritt and was among the “notable bottlenecks within the city grid.”6 If Oakland was to become a beautiful city of rational planning, the groundwork would be laid on boulevards like 12th Street. The bottlenecks must be removed.

One hundred years after Bartholomew gave his speech, I am crossing 12th Street on foot. It is a February morning and the sunrise smudges through the fog across the eastern sky, casting a muted light over the concrete sidewalks.

I’m jogging toward Lake Merritt through the bottleneck that Bartholomew noted. Except it isn’t a bottleneck anymore. It is an expanse of tarmac. Seven lanes converging into a broad sea of asphalt at the intersection of 1st Avenue and East 12th Street.

Crossing this intersection on foot is uncomfortable. Both roads curve with slight rises, reducing visibility. You feel exposed in the crosswalk—a creeping sensation that a car is speeding into you rests at the edges of your awareness.

Because it is so large, as wide as a football field and a third as long, cars can accelerate to high speed. So cars buzz past, oblivious to humans in the street.

In terms of traffic problems, this intersection is not particularly notable, nor especially deadly; more pedestrian fatalities occur elsewhere in Oakland. Unlike Interstate 880 a few blocks away, 12th Street no longer makes the rush-hour traffic report.

And yet it is emblematic of the discomfort and danger of pedestrians in American cities. Intersections like these are zones of disinterest for those on foot.

Surely, you’ve felt it yourself. To run or walk or bike through an urban space simmers with violent possibility. Crossing a street on foot in the United States can feel like trespassing because you are moving into space that is not designed for you. It is a space of collision, hostile to human life.

There are thousands, likely tens of thousands, of intersections like this across America. Sure, many have crosswalks, but what is a crosswalk except paint on the ground? And what is paint in the face of wide rivers of metal, glass, and plastic flowing at high-velocity?

Since we moved to this neighborhood in Oakland, I have crossed the 12th Street intersection nearly every day. And over the years I have wondered why it is so wide. How did it become so difficult to cross on foot? And what can this intersection tell us about why American roads are so hostile to pedestrians?

Let us return to the beginning.

By the time Harland arrived in 1924, there was undoubtedly a problem. 12th Street’s original crossing was built across the tidal outlet of Lake Merritt in 1863.7 Over the next half century, more and more people moved into and through Oakland, often from across the region, and increasingly by carrying their bodies within metal, motorized vehicles.

The only option to reach the rail lines that connected the Bay with the continent to the east, to reach the wharfs that led to the Pacific, and to reach the ferries that shuttled to San Francisco was through Oakland. Funneling into 12th Street, an entire region of traffic converged on a single roadway, the only street crossing of Lake Merritt. At peak hours, it was nasty. Snarls of traffic built up in both directions.

Heeding Harland’s warning, the city worked to create two widened boulevards across Twelfth Street. Various proposals were floated to use land in front of the city’s municipal auditorium for the needed street expansion. Street cars from the Key System would be shunted down the center of the street, freeing traffic on either side. These schemes were intensely contested in the City Council, as were the various assessment plans to pay for the new roadway.8

Even as Oakland’s leaders haggled, they hired Harland Bartholomew’s engineering firm to create a definitive plan for Oakland’s traffic system. The resulting report in 1927 proposed a radical new paradigm for what a city could and should be.

In A Proposed Plan for a System of Major Traffic Highways Bartholomew reframed the principles that guided the design of urban space. Crucial to the commercial, social, and political wellbeing of a city was the movement of its people. His transportation plan aimed “to promote a gradual, progressive modernization of the Oakland circulation system.”9

The circulatory reference is telling. It reflected a perspective that grew to dominate the urban reform movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Europe and the United States: that urban places, where people inhabited, worked, and co-existed, should be understood as circulatory space.10 Healthy cities moved people efficiently. And efficient movement required rationalized streets, avenues, and highways.

Planners compared the modern city to a corporeal body. "Inadequate Streets Like Hard Arteries” trumpeted the Oakland Post Herald in January of 1923 over an op-ed from Dr. Carol Aronovici, a Romania-born city-planning expert. ”It has been found,” Aronovici wrote, “that business increases rather than decreases as the streams of traffic are released.”

Flow was the crucial economic dynamic: “it is not a matter of the number of persons or vehicles contained on a given area in a given period of time,” argued Aronovici. “Rather of the number of persons or vehicles passing at a given point in a given time.”11

As within a human body, these clots were dangerous. They disrupted life-giving circulation, enervating a city’s economy and people. Bottlenecks of traffic were “congestion,” “blockages,” and “jams.” The same language that was used to describe heart disease. The challenge was releasing the flow that enabled commerce and prevented the stagnation of inhabited space. Planners like Aronovici, however, did not consider the inhabitants themselves. How the people actually living in and around these arteries would be affected by the removal of traffic blockages often went without note.

Improving city circulation meant street widening, a policy that would fundamentally alter urban space once used by a mixture of trolley riders, drivers, and pedestrians. Street-widening efforts began to reshape the contours of American cities. Buildings were shifted, frontages removed, sidewalks narrowed. People on foot, in Oakland and around the nation, were forced to the edges of public space, relegated to sidewalks along a narrow sliver of street.

For Twelfth Street, “the crux of Oakland’s present traffic problem,” Bartholomew proposed widening the size of this vital artery. Aspects of Bartholomew’s 1927 plan were not followed, including traffic circles to remove the need for left turns, but its width was to be widened from 120 to 220 feet.12

Similar widening projects occurred elsewhere in the city, the state, and the nation. Roads widened. Flows of motorized drivers increased. Bodies on foot yielded way.

One century later, on a pleasant weekend morning, my wife went out for a run, crossing the intersection of 12th and 1st. She was pushing our child in a stroller. The light changed, the pedestrian signal shined.

As she pushed the stroller across the crosswalk, she was beset by a driver also trying to cross the intersection in his car. Caitlin had the right of way, but the driver was enraged at the inconvenience of having to wait for her to cross. He blasted his horn and pulling the car to the shoulder, got out and shouted at her. Caitlin quickly walked away, shaken.

It’s easy to blame the man, in his wheeled arrogance, for claiming right to the space my wife was taking on foot. This anger seems irrational. But in the hierarchy of space created by men like Bartholomew, such ugly behavior makes a certain sort of sense. The street was designed for cars. To allow people to cross them on foot is mere accommodation. Yelling at pedestrians is bad behavior. But people are only as good as the designed world allows them to be.

This is not just about one rude driver; it’s about a larger system that subtly shapes behavior through its very design. After a century of car-centered design, much of the urban world is unfit for the human body. We feel it in the slight tension in our chests as we move along six lanes of traffic on a narrow sidewalk. We feel it in the reflexive whipping of our heads left-right-left at crossings—an involuntary tic of American modernity, instilled from childhood. These are signs of distress, of a body-politic deeply unwell within the spaces it resides.

In 2024, we need to recognize that the rational society created by the urban planners is, in fact, insane. It is a society in which 41,000 Americans were killed in traffic deaths in 2023, mostly without comment, a society in which mothers and children must be admonished for the temerity of crossing a street. It is a society that has lost its mind.

All of this to widen a street. To fix a bottleneck. To make a city fit for cars.

But even this widening would not be enough. Planners like Harland Bartholomew were not finished with Oakland.

Read part two of this essay:

A special thank you to the staff at the Oakland History Center at Oakland Public Library for helping access newspaper collections that informed this piece. Additional thanks to the Oakland Heritage Alliance for sourcing several photos. OHA leads historical tours throughout the town as part of their work to advocate for Oakland's architectural, historic, cultural, and natural resources.

To learn more about the development of Oakland’s cityscape, check out Hella Town: Oakland's History of Development and Disruption by Mitchell Schwarzer, professor emeritus at California College of the Arts. You can listen to ’s podcast episode with Schwarzer, which discusses the town’s car-centric development. For a more general survey of Oakland’s history, see Beth Bagwell’s Oakland: The Story of a City.

If you’d like to support Footnotes, consider upgrading your subscription or sharing this newsletter with a friend. Footnotes is a labor of love, but it is labor. So I’m immensely grateful if you could help spread the word.

“Streets Inadequate for Growth,” Oakland Tribune, February 19, 2024, 28.

"The Whole City Is Our Laboratory": Harland Bartholomew and the Production of Urban Knowledge, Journal of Planning History 4, no. 4 (November 2005): 322-355.

New York Times, "Harland Bartholomew, 100, Dean of City Planners," December 7, 1989. "Harland Bartholomew," The Cultural Landscape Foundation, accessed June 23, 2024. On planning the District of Columbia see Chapter 10 of Harland Bartholomew: His Contibutions to American Urban Planning.

“Famous Planner Coming,” Oakland Tribune, January 6, 1923, 17.

"City Advertising Plan Discussed," Oakland Tribune, December 9, 1923, 21, “Famous Planner Coming,” Oakland Tribune, January 6, 1923, 17.

“Streets Inadequate for Growth,” Oakland Tribune, 28.

Horace Carpentier built the first crossing. At the time, the “lake” had not yet been dammed and the tidal lagoon had much more fluid boundaries. Beth Bagwell, Oakland: The Story of a City (Novato, CA: Oakland Heritage Alliance, 2012), 47-48.

“City Creates Fund to Break Twelfth Street Bottleneck,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 18, 1926; "Dam Work Begins Tomorrow," Oakland Tribune, September 15, 1926; "Traffic Problem Solved," Oakland Tribune, September 19, 1926, 6B.

A Proposed Plan for a System of Major Traffic Highways, Oakland, California, 1927: For the Major Highway and Traffic Committee of One Hundred. United States: Harland Bartholomew & Associates, 1927. Available online.

Jane Jacobs’s outline of this story is a fine, if caustic, starting point for understanding how Garden City and Radiant City theories of city design shaped the worldviews of planners like Robert Moses and Harland Bartholomew. Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 2011), 23-34.

"Inadequate Streets Like Hard Arteries," The Oakland Post Enquirer, January 8, 1923, 1,5. My emphasis.

Bartholomew, Proposed Plan, 16-71; Mitchell Schwarzer, Hella Town: Oakland's History of Development and Disruption (Oakland: University of California Press, 2021), 95.

Really enjoyed this and learned so much... if only we could have a similar transformation to make walking out your door to walk around your own city safer. I like to think that running has made me a more conscious driver but you're right, the car always has the power. Excited for part two!

Bravo on your research and the historical photos. I miss running Lake Merritt but not the intersections at Grand or Lakeshore to get there.