Don't Trust the Process

The peril of living like a clock.

The opening moments of David Fincher’s film The Killer are quiet.

Michael Fassbender, playing the titular role of an unnamed assassin-for-hire, waits in solitude. He stakes out a mark in Paris, observing the target’s apartment through a rifle barrel.

The Killer watches from an abandoned WeWork office. He sits, he stretches, he waits. Silent. Meditative. Short stints of sleep disrupted by a heart rate monitor, which chirps when it drops too low.

“This is what it takes,” he tells us repeatedly in voiceover monologue. Performance is just process:

“I’ve come to realize that the moment when it’s time to act is not when risk is greatest. The real problems arise in the days, hours, and minutes leading up to the task and the minutes, hours, and days after. It all comes down to preparation, attention to detail, redundancies, redundancies, and redundancies.”

On its surface, the movie is another antihero story about a gun-for-hire. But we soon learn The Killer is a man of his time, an exacting creature consumed by his craft.

His diet is regimented and utilitarian. “There are 1,500 McDonalds in France,” he observes, “a good enough place to grab ten grams of protein for a euro.” Later, he scarfs down a plastic-wrapped hardboiled egg, washing it down with gas-station coffee. Food, purged of pleasure, purely caloric.

The Killer is process refined. No movement wasted. Every effort focused on the next task to complete the next goal. Pleasure excised because “this is what it takes.”

“And remember what Jumbo Elliot used to tell the Villanova guys.”

“What was that?”

“Live like a clock.”

“Live like a clock?”

“What Jumbo meant was keep to your schedule. If your morning run was always at eight A.M., you go out and do a token run at eight A.M., even if you’re tapering for a big race or on summer break . . . Eat at the same time, sleep at the same time. Live like a clock.”

— Once a Runner

Process is big these days. “Focus on the process,” admonish coaches, whether they’re coaches of sport, life, or career. Don’t get caught up on the end result, they advise. Rather focus on the work at hand, embracing the small practices and tasks that carry you to the result.

“Live like a clock,” admonished Jumbo Elliott, the track and field coach at Villanova quoted in Once a Runner. Elliot knew something about performance; he trained 5 Olympic gold-medallists in the 1950s and 1960s. Clocks don’t ponder their endless rotations around the dial; they just spin, consistently, relentlessly, perpetually, redundantly. And so must athletes.

Great athletes, world-beating athletes, don’t rely on one Super Mega Workout. There is no secret formula, no Rocky montage of upside-down sit-ups, dangling from the barn rafters. No, there is only a hundred-thousand steady efforts, slowly whittling flesh and mind into an instrument of purpose.

To be good, to be really good, you must be like the clock: ever rotating, optimizing, and training. Focus on the small gains, incremental improvements. You might not have to choke down the sulfuric taste of plastic-wrapped gas-station egg (although I once did before an evening 10K), but you will have to be comfortable with discomfort. This is what it takes.

Lately I’ve been pondering process.

The crunch of new parenthood makes carving time for writing and running a challenge. So I wake up earlier. My wristwatch buzzes at 4am and I think of Jumbo’s mantra—Make yourself a clock—as I claw out of bed.

It hurts. The body’s systems push back, try to prevent the severance of sleep. Alarms klaxon deep in my brain, calling for rest. But I’m at a middling age now, when mediocrity creeps around the edges of every endeavor, and this horrifies me.

So I trust the process and run groggily around Oakland’s concrete-shouldered lake, tedious laps in the gloomy matins before dawn.

As I jog along, I’ve begun to wonder, to what end? To what purpose is all this? And what do we lose by sacrificing ourselves to the clock?

Consider the Ingebrigtsen family, a trio of father-coached brothers who have made waves in the world of distance running. The Norwegian brothers—Henrik, Filip, and Jakob—each boast impressive resumes after years of steady improvement. Both Henrik and Filip earned titles and medals at European and World Championships. Jakob, the youngest brother, has shattered world records and won a gold medal in the 1500m at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

Their 2019 reality-TV series “Team Ingebrigtsen” shows an entire family dedicated to the goal of getting the boys faster. Siblings and partners travel with them to training camps and track meets around Europe. Filip notes his mother “has washed thousands of kilos of sweaty training clothes.”

A 2019 study of the Ingebrigtsen brothers confirmed this totalistic focus. By their teenage years, they were training over 110km per week. Jakob trained daily at age 12. By 17 that was upped to 13-14 weekly workout sessions.

“We asked our father for permission to do some morning sessions in addition to the afternoon sessions. We were allowed, but our father said that we should not tell this to our teachers, they would worry and think he was pushing us too hard.” —Filip Ingebrigtsen

This process yielded results. But not without cost.

Last autumn, the brothers spoke out in the Norwegian tabloid Verdens Gang, lambasting their father Gjert, “who has been very aggressive and controlling, and who has used physical violence and threats as part of his upbringing.” Gjert Ingebrigtsen strongly denies this, but for brothers, in their own words, “the joy of playing sports is gone.”1

It’s a troubling development, one that reveals what’s risked when we focus too much on process. We stop asking why exactly we’re working so hard and what we’re willing to sacrifice along the way.

Without pondering those deeper questions, I think we risk a myopia of the spirit. And the peril goes beyond sport. Life becomes an exercise in squeezing more efficiency out of our limited hours, in studying how to work or train better, in berating our athletes or our employees or ourselves to work ever harder. We push more, always onwards, always forward, never pausing to wonder, “To what end?”

And in our restful moments, the few we’re willing to afford ourselves, we’ll sit next our loved ones. We’ll put on a smile, just for a moment. But eventually, inexorably, we’ll set our faces toward the next task, eyes twitching under the strain.

Sic semper laboribus.

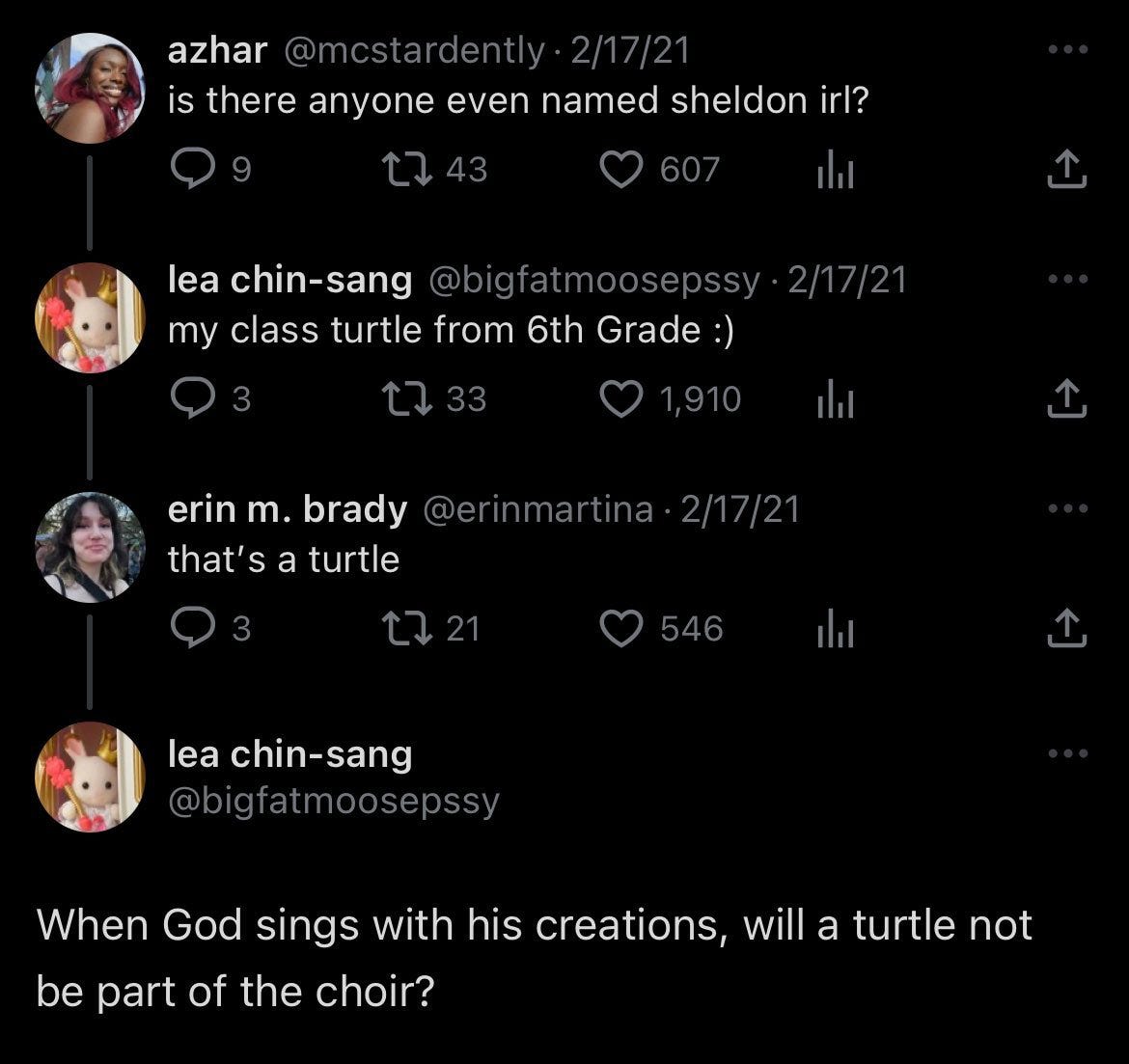

Tweets of the week

Parting thought

“Bruce, I’ve been doing that very thing for years now . . . I’ve lived like a clock for nearly four years in college, through quitting school and racing Walton, through the buildup for the trials, and then right to the finals of the goddamn Olympic 1500 meters.”

“Right.”

“And you’re telling me . . .”

“To keep doing it.”

— Once a Runner, John L. Parker, Jr.

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading. You can follow me on Notes, Strava, and what’s left of Twitter.

Coincidentally, the Ingebrigtsen’s made their statement on October 20, 2023, one week before the limited theatrical release of The Killer.

Lovely meditation. I just wrote something about that “why” question. I think if one starts with it, answers it honestly (even when it’s uncomfortable) and re-examines it every time it seems like one’s life might have outgrown it, that absolutely vital process is an armature for building on, not a prison to languish in.

This may be my favorite thing you've ever written, Sam 👏 👏 👏