The sun rises over Lake Temescal like a painting.

Shades of pink and orange, the watercolors of dawn, blur through the fog along the escarpment of the Oakland hills, drawing color down into the rift valley below. For a moment, confronted with this technicolor canvas, you wonder if this is artifice, some painted background for a cinematic tableau.

Lake Temescal itself is indeed an artifact, the result of an earthen dam tossed against a canyon creek in 1868.1 Once a reservoir, now a splendid gem of parkspace improved during America’s brief flirtation with social democracy in the 1930s. A stately beach house, built by the Works Progress Administration, stands watch over the pooled water of Temescal Creek. Some days, fog lingers over the water beneath sheer cliffs above the western shore like an emerald lagoon within some Sierra forest.

But if the Lake is a gem, it is a jewel ensconced in a crown of freeways.

Should your eyes drift down from the auburn hillside, they’ll settle upon a wall of concrete, one funneling thousands of wheeled bodies toward the city below. Massive supports rise up from the lake’s eastern banks. Head north from the lake and you’re confronted with a thirty-foot wall of stone and concrete. Beyond this are nine lanes of the Grove Shafter Freeway.

To cross this freeway, you must turn up or down the hillside, following the frontage over a half-mile up to an overpass or down to underpass. This means crossing the highway on foot or bike requires over a mile of distance traveled.

It’s a small diversion, but think about the implications at scale.

Consider, for example, a small running club that has met at the lake for nearly a decade. It averages around ten people in attendance from week to week. That’s an extra 10 miles or so collectively for the group each week. Over the course of a year, that diversion adds up to around 450 miles. Over a decade? An extra 4,500 miles of movement.

Imagine how much travel has been impacted when considering the thousands of people living in the neighborhood, the tens of thousands within the broader zip code, the hundreds of thousands within the city. The amount of extra movement spans into the hundreds of thousands, possibly millions of miles of forced movement since the freeway opened in 1985. This is the impact of a single freeway on a single neighborhood.

I never intended to think about freeways. I was just curious why an intersection near my house was so wide.

In part one of this story, I discussed how Oakland’s streets were widened for a new paradigm of human movement: traffic, which flowed and circulated through a city, reordering how urban space was valued and who deserved primacy within that space.

I focused on a single intersection, the confluence of 1st Avenue, East 12th Street, and Lake Merritt Boulevard, examining the history of urban planning in the first decades of the twentieth century and how it was brought to bear on a small section of Oakland.

To tell the full story of how this intersection became hostile to runners, walkers (and humans more generally) we need to return again to the past, this time to the postwar years, a moment of optimistic urban reconstruction, energetic building, and miles upon miles of freeway.

This is an Oakland story, but it’s also an American story. Because the transportation changes that set Oakland on a path of sustained social erosion was a process that left few American neighborhoods untouched.

In 1947, Oakland was flush.

Flush with industry that helped defeat the Axis powers. Flush with GIs returning home. Flush with labor in high supply. Flush with demand for goods and limited housing.

It was also flush with automobiles that made traffic nightmarish.

During this year of demand, Harland Bartholomew, an urban planner from St. Louis, returned to the East Bay with another plan to bring the city into the future. It was an update to his transportation schema from two decades earlier.

In A Report on Freeways and Major Streets in Oakland, California, Bartholomew’s engineering firm held that ordinary surface streets were no longer sufficient for the automobile. Despite street widening, a process that had demolished buildings and narrowed sidewalks, congestion now forced car traffic “to travel at slower speed than was possible in the days of the ‘horse and buggy’” during peak hours. Somehow the city’s movement was stagnating.2

According to the report’s calculations, population growth and an increase of percentage of car ownership, the report estimated that traffic trying to cross the city’s junctures around Lake Merritt would rise to 407,000 vehicles per day by 1970, a 90 percent increase from 1946. Congestion would only worsen.3

The solution was the “freeway,” an express highway that allowed travel on wide, mostly straight roadways where cross traffic at grade was eliminated, meaning cars could travel without intersections. Cross streets were carried over or under the roadway; access to the freeway was limited to strategically placed ramps.

Parkways and expressways had existed for some time.

The first stretches of autostrada were built in Italy during the 1920s. Hitler was enthusiastic about the wide roadways of the autobahn, designed to let fast-moving automobiles fly between the cities of the Reich. On the east coast, Robert Moses knit Long Island into an exurb of New York City in the 1920s and 1930s with the Southern and Northern State Parkways.

Up until the postwar 1940s, no one had considered running freeways through a city. But as a member of the National Inter-Regional Highway Committee, formed in 1941, Bartholomew was deeply informed of the principles and plans for implementing this interstate highway system within urban areas. Interstates would not only speed automobiles between cities, they would also bring automobiles directly through cities.4

Bartholomew’s team proposed a system of interworking freeways around Oakland. The centerpiece of this second plan was a series of expressways that would allow automobiles to completely bypass Oakland’s city streets.

Anchored upon the eastern portal of the Bay Bridge, freeways would extend outwards to the hillsides along MacArthur Boulevard, shoot to Contra Costa County over Shafter Avenue, and run between the downtowns of Oakland and Berkeley atop Grove Street. Freeways would stretch along the entire East Bay shoreline, cut through West Oakland, and wrap around Alameda Island.

Finally, a short expressway would improve downtown Oakland’s connection to its eastern neighborhoods. This particular freeway, while short in distance, would correct Oakland’s long-time bottleneck on 12th Street, where congestion persisted.

Prior to Bartholomew’s general plan, Oakland City Engineer Walter Frickstad created a plan to resolve the bottleneck through a radical expansion of street width with the “channelization” of car traffic to eliminate crossings and left turns. Bartholomew assessed this traffic-separation structure as “satisfactory.”5

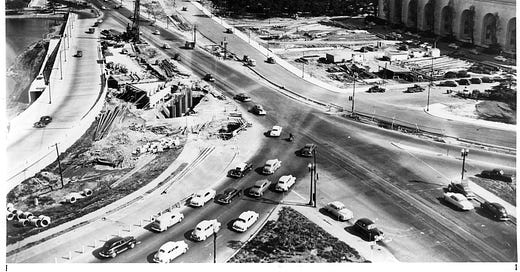

In 1949, work began to realize the plan. Piledrivers drove the foundations of the roadway into the mud of Lake Merritt’s tidal lagoon. Street car tracks that ran trolleys over the dam were ripped up and the existing boulevard replaced by 12 lanes of traffic, woven over and under each other in braids of concrete.

The total cost of the expansion was $3,000,000 but it was, the Oakland Tribune noted, the “solution to Oakland’s 25-year-old headache, the 12th Street Dam bottleneck.”6

On June 16th, the final element of the solution was opened to automobiles. The Frickstad Viaduct, which originally referred to the two lanes along Lake Merritt but came to be the name for the entire structure, was completed.7

The viaduct twisted across the space between the lake and city auditorium in a spaghetti of traffic lanes weaving across each other in interwoven ribbons. Pedestrian crossings were replaced by underpasses to the lake beneath the twelve lanes. But accessing those tunnels was difficult, making entire spans of lakefront difficult to reach on foot. Citizens were thus separated from their main central park by hundreds of feet of roadway.8

Over the next four decades, freeway projects like the Frickstad Viaduct continued.

Oakland would blitz through itself, moving and condemning hundreds of houses to carve out I-580, Highway 24, I-880, the Cypress Street Viaduct, and Highway 13. These cut through the city’s core neighborhoods. It was, to borrow a phrase from Robert Caro, urban planning with a meat axe.

Beyond the immediate impact of the freeways’ construction, the highways turned the city into a sort of turnstile.

They accelerated the trend of the upper and middle classes to move beyond the city’s main districts, to the hills of Oakland, Piedmont, and beyond into Contra Costa County, where the managerial elite could retreat to the comfortable idiocy of suburban life.

Oakland—like Boston’s West End, St. Louis, South Bronx, Queens, southwest Philadelphia, Baltimore, and many other cities—was redesigned as a greyscape through which the moneyed classes would commute on their way to well-paying jobs in the city center or San Francisco. The freeways, intended to help the city by removing surface-street traffic, served to undermine them.

Mitchell Schwarzer has noted that Oakland automobile infrastructure produced new modes of mobility particularly reflective of class and race. Access to points across town became privileged for car owners. Moreover, wide streets and freeway-based transport emptied Oakland’s sidewalks. Fewer pedestrians meant fewer eyes watching the streets. Small wonder that by the 1960s, after the East Bay freeway system was mostly completed, crime began a decades-long increase. Oakland’s pedestrian vitality had been diminished.9

Sixty years after the Viaduct was completed, there’s a lifelessness around the southern shore of Lake Merritt.

A modest parking lot rests beneath the reconstructed auditorium. A broad grassy area stretches from the lake. There are few trees and fewer people. But for the random smoker, sitting along the concrete crescents that make up a low-slung amphitheater facing the lake, those enjoying the waterfront rarely linger. Most pass by along the lakeside path.

The area feels bleached and stunted. Indeed, this space is in a sort of semi-recovery. In 2010, work began to remove the Viaduct. Funded by Measure DD, a ballot measure to fund park improvements, the city removed six of the lanes to restore a two-way road, now named Lake Merritt Boulevard. While the pedestrian improvements are significant and laudable, six lanes remain. The boulevard and its intersections remain difficult to cross. Even still, the road is narrower.

But this narrowing is not enough.

Resting beneath the world we inhabit are decisions that shape how we move through a place. Those decisions reflect political power. It’s not the power we usually think of regarding politics, the stuff discussed during elections and by candidates running for major office. This power manifests through layers of bureaucracy and complex funding mechanisms. It’s mediated through local, regional, and state institutions. It’s often executed by private firms. It is power that’s difficult to understand. But it is power nonetheless.

It is power that forces you to wait compliant at an intersection, to yield the right of way to wheeled metal, or to risk citation, injury, or death by choosing not to yield. And that is the essence of power: the ability to determine which bodies, under which conditions, get to move, and which must wait, adjust their course, or not move at all.

Understanding how that power manifests means unpacking chains of history—the history of ideas, the history of cities, and the history of economies. But that is a worthy effort because we are the inheritors of those chains, anchored to a concrete legacy that will be exceedingly difficult to undo.

Thanks for reading. You can read the first part of this essay here:

Get Footnotes sent right to your inbox by subscribing. To support this work, consider upgrading your subscription.

Much of this two-part essay was inspired by Robert Caro’s The Powerbroker and Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Reading these books for the first time this year helped me see urban space in new ways. So I’m grateful for 99 Percent Invisible’s Power Broker Book Club, which spurred me to finally crack open Caro’s massive biography of Robert Moses. Those interested in Oakland’s 20th century development should read Mitchell Schwarzer’s Hella Town, a highly accessible examination of the town’s economic, social, and infrastructure development. I’m incredibly grateful to these writers, scholars, and creators for helping spark new questions and curiosity for me.

Chinese immigrants built the dam at Lake Temescal through a process called "puddling," which uses horses to trample the earth. Workers first removed tons of wet clay and dirt, digging deep to find bedrock for the dam's foundation. Then the dirt-clay mix was pressed down by mules and horses, creating a watertight concrete-type material. “Chinese Workers and the Easy Bay’s Early Water Systems,” FireHydrant.org, accessed September 28, 2024, http://www.firehydrant.org/info/ebchina.html.

Harland Bartholomew and Associates, A Report on Freeways and Major Streets in Oakland, California, prepared for the City Council of the City of Oakland, California, July 1947, 20.

Bartholomew, Report on Freeways, 17. What Bartholomew and other mid-century planners did not understand was induced demand. Increasing road space (and disinvesting in public transit) encourages more people to drive, thereby exacerbating traffic rather than reducing it.

Bartholomew, Report on Freeways, 20-21.

“City Council to Hear 12th St. Traffic Plan,” Oakland Tribune, April 16, 1946, 1, 5; Bartholomew, Report on Freeways, 32. The street expansion at Lake Merritt was consider part of the larger project of freeway enhancements to the city’s roadways. An editorial in the Oakland Tribune labeled the 12th Street improvement “a component part of the broad State-approved program for freeways,” in “Public Will Hold Council to Account,” Oakland Tribune, March 2, 1946, 16D.

“12th Street Dam Unit Opens Tomorrow” Oakland Tribune, Sunday, March 22, 1953, 11A; “12th Street Dam Project To Be Ready Early in ‘53,” Oakland Tribune, Sunday, October 14, 1951, 32A

"12th Street Dam Structure to Open Tomorrow," Oakland Tribune, June 15, 1953, 1A.

In many ways, the Frickland Viaduct encapsulated in miniature a tendency for mid-century highway development to occur along waterfronts, effectively blocking citizens from their coasts, lakes, and rivers. Lambasting the Henry Hudson Parkway in the 1960s, Peter Blake wrote, “In place of great parks and terraces and promenades, we have built, along almost every single foot of the coastline of this city, gigantic viaducts of steel and concrete that carry streams of automobiles and effectively block our views of the water, a passing steamer, a seagull or, possibly, a sunrise.” Peter Blake, “How to Destroy a City,” New York Herald Tribune, March 13, 1964. Cited in Robert Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1974), 561.

Mitchell Schwarzer, Hella Town: Oakland's History of Development and Disruption (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2021), 102-105.

I used to run around Lake Merritt multiple times a week, starting at the south side. you can access it via a pedestrian path that goes under that bridge, or cross pretty easily a few blocks away. The bridge is also pretty easy to cross on a bike if you know what you're doing and are comfortable asserting yourself in the lane. It's a pretty low-traffic area anyway (or was until 2020 when I left). On a sunny weekend the walking path on the south side of the lake was bumping with fixie kids playing music and practicing spins. The route to Temescal felt pretty natural from all directions except northeast of 24 in the hills (where few were coming from anyway).

It's good to tell stories about urban development and the compromises developers had to make so they could build. But to describe traffic laws as assertions of power surely doesn’t tell us anything interesting about their political legitimacy. Of course they are assertions of power, just as judicial orders are assertions of power.

The more interesting question is what it would be for these assertions of power to be unjust. It's not obvious to me from the story you've told that the plans were unjust. Poor design in several cases, and technologically hamstrung, but unjust?

I press the points only because the left is going to have to find new ways of relating to Robert Moses' legacy as they respond to demands for Abundance. In Oakland, for example, what level of political opposition from special interest groups, nimby's, and environmentalists would we tolerate if we tried to massively expand safe, quality, and fast public transportation; or rail; or tunnels? What if we wanted to build that stuff fast?

Comfortable idiot here. Oakland was my home for many years before OUSD pushed us through the tunnel. Our first place was in Temescal and the lake is kind of magical and unexpected in the hubbub. Also dug Lake Anza